JANM Campus

Architectural History

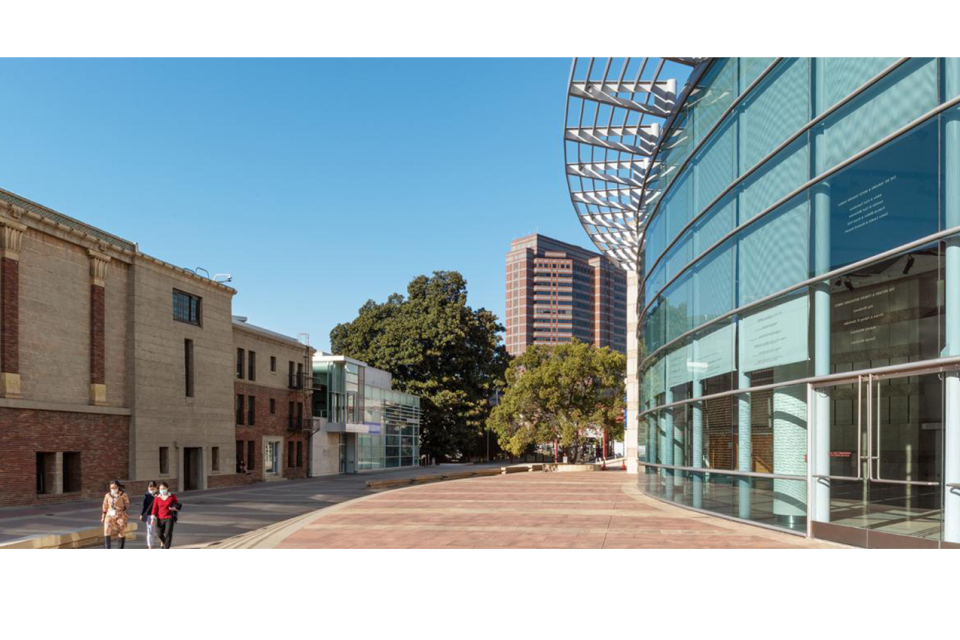

JANM’s campus in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo consists of the Historical Building, the Pavilion, the Daniel K. Inouye National Center for the Preservation of Democracy (Democracy Center), and public art installations that are all connected by the expansive Norman Y. Mineta Democracy Plaza. Built in 1925, the Historic Building was a former Buddhist temple that has undergone several renovations and an expansion that reflects the changing face of Little Tokyo. The Pavilion was built to house more gallery, collection, and gathering spaces needed for a world-class museum. The Norman Y. Mineta Democracy Plaza physically and visually connects all of the structures together and provides a gathering space for the public.

Historic Building

JANM’s renovated Historic Building was formerly the Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist Temple, the first Buddhist temple building constructed in Los Angeles in 1925. Financed at a cost of $250,000 by the Los Angeles Hompa Hongwanji Buddhist Temple, it is a unique structure designed by local architect Edgar Cline. The building combines an eclectic mix of architectural styles, including Japanese and Middle Eastern, which were popular in the United States in the 1920s.

Besides its primary role as the focus for the local Buddhist community, the temple building served as a social center because its hondo or main hall, where services were held, also functioned as an auditorium. That space served as a community venue for live performances and movie screenings.

The building’s frontage on First Street contained three floors of rented office spaces which housed restaurants and small businesses, providing income for the temple. These spaces were physically separated from the temple. The temple’s main ceremonial entrance was located on Central Avenue, which connected to the hondo upstairs and the social hall downstairs. The third section of this asymmetrical structure was the living spaces for the temple’s minister and family. Situated at the northern most point of the building, this third section had its own separate entrance.

When World War II began, the Japanese American population was ordered to leave their homes and businesses by the U.S. government. That included the temple’s staff except for Rev. Julius Goldwater, who had converted to Buddhism before the war. The temple building was used as a storage facility for its members’ property, who could only take what they could carry during their forced removal. When the government began releasing Japanese Americans from concentration camps as the war ended in 1945, the temple building operated as a hostel for those returning.

In the 1960s, the City of Los Angeles’s Civic Center was undergoing redevelopment and it notified Nishi that it could affect their facility. The Los Angeles Hompa Hongwanji Buddhist Temple began looking for a site to construct a new temple and campus. In 1966, it purchased the property at the corner of First Street and Vignes and began construction in 1968. After completing the project in November of 1969, the temple left the original structure and sold the building to the City of Los Angeles in 1973.

The former temple building fell into disrepair over time. After the Japanese American National Museum was incorporated in 1985, it signed a 50-year lease the next year with the City of Los Angeles to renovate the structure and convert it into a museum with dedicated spaces for exhibitions, collections, and public programs. In October 1986, the historic building was designated as a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument.

Given the former Buddhist temple’s historic status, the renovation became more time consuming and expensive than originally estimated. To bring the building’s structure up to modern earthquake code, it was necessary to center-core into the brick walls from the roof to ground level. 28 six-inch diameter core holes were drilled, steel No. 9 rebars were inserted, and the holes were packed with epoxy fill. This allowed the brick walls to flex and not collapse when the 1994 6.7 Northridge earthquake caused millions of dollars of damage to similar structures.

To make use of the entire structure, the First Street frontage offices, where JANM staff worked, were connected to what was once the temple. An elevator was installed and the stairway was extended to connect to the second and third floors. The former minister’s quarters were transformed into a collection space and photography dark room. After JANM opened in 1992, the renovated Historic Building was the site of groundbreaking exhibitions, public programs, and social gatherings. It also hosted Their Royal Majesties, the Emperor and Empress of Japan in 1994. In 1995, the historic building, along with the north side of First Street stretching all the way to the old Union Church structure on Judge John Aiso Street, was designated as part of the Little Tokyo Historic District by the National Register of Historic Places.

The Pavilion

Soon after the Japanese American National Museum opened to the public in its renovated Historic Building, it made plans to develop an adjacent modern structure to expand its exhibition and collection space and work facilities. The Board of Trustees engaged famed architect Gyo Obata, principal of Hellmuth, Obata and Kassabaum (HOK), to design the expansion.

Obata, who designed the National Air and Space Museum at the Smithsonian, conceived of the 84,000-square-foot Pavilion in relationship to JANM’s Historic Building. Gyo, whose father Chiura was an Issei artist, chose exterior and interior building materials that expressed a Japanese aesthetic that favored wood, stone, and glass.

“In designing the Japanese American National Museum’s new Pavilion, we sought to create a sense of openness instead of the conventional front-of-the-house/back-of-the-house division of so many museums,” explained Obata. “We also worked to incorporate both Western and Eastern philosophies in the design and to create a structure that was inviting and reflective, as witnessed in the use of glass and perforated stainless steel that softens direct sunlight.”

Yellow Italian granite in honed, flamed, and sandblasted finishes were used for the Aratani Central Hall wall, reminiscent of the Historic Building’s exterior. Cleft-finished red Indian sandstone constituted the wall on First Street that borders the Hirasaki Family Garden. The two walls, evoking the two waves of JANM’s mark, come together at the JANM Board Room and Museum Store, symbolizing the fusion of Japanese and American influences.

High-performance tinted and laminated glass enclose the George & Sakaye Aratani Central Hall and the south galleries, the latter protected by a screen of perforated stainless steel. It conveys a sense of openness and transparency to balance the stone walls. In the interior, the Indian sandstone wall rises above the two-story Manabi and Sumi Hirasaki National Resource Center (HNRC).

HOK interviewed JANM staff to prioritize function within the Pavilion, including two stories of collection/archival storage at the “heart” of the building as well as a multimedia production center with a sound-edit bay and darkroom for the Frank H. Watase Media Arts Center and an exhibition design studio and fabrication shop. A driveway connects to a loading dock at the north side of the Pavilion.

On the public side, the Pavilion created over 18,000 square footage of new gallery space and the two-story 4,000-square-foot Aratani Central Hall which was designed for temporary exhibits, lectures, and special events. The Aratani Central Hall features a wall of reflective glass through which the Historic Building can be seen. The Mineta Democracy Plaza extends the space of the Aratani Central Hall, linking it to the Historic Building with its stepped podium that provides an informal amphitheater. The Aratani Central Hall floor design, made of terracotta, extends through the glass wall into the plaza and reaches out to the Historic Building.

“The Pavilion’s interior incorporates the old and the new, and includes traditional naturally lighted galleries, as well as larger galleries for contemporary works and installations,” Obata said. “Other interior features include a sweeping grand stairway, cherry wood paneling, a convenient centrally located collection space, and expanded areas for educational programs, library facilities, and offices.”

Besides two large classrooms, the Pavilion features the unique two-story Hirasaki National Resource Center (HNRC) as the public access to the JANM collection. The HNRC holds an archival viewing room, a mezzanine, and the Life History Studio. Connected to the downstairs gallery is the Terasaki Orientation Theater.

Between the JANM Store and the Paul I. and Hisako Terasaki Garden Café space is the Manabi and Sumi Hirasaki Family Garden, created by landscape designer Robert Murase. While the garden features Carnelian granite from Minnesota and Arizona flagstone, it also contains fragments of what was the existing sierra granite curb installed into the water fountain as a connection to the site’s past. The 90-foot-long fountain with its water hitting stone is the sound of nature in the middle of an urban setting.

“In designing the courtyard and garden for the Pavilion, I drew inspiration from the ancient and sacred tradition of stone, from the stone walls and megaliths in Europe to the stone gardens of Japan,” Murase revealed. He also was inspired by the work of the late Japanese American sculptor and landscape designer, Isamu Noguchi.

Daniel K. Inouye National Center for the Preservation of Democracy

Founded in 2000 as the National Center for the Preservation of Democracy, JANM’s initiative was relaunched in 2023 and named after Senator Daniel K. Inouye. The Democracy Center embodies the senator’s vision to inspire all Americans to engage actively in the shaping of democracy.

In 2005, JANM received a federal grant to complete the construction of the Democracy Center as an addition to JANM’s Historic Building. The project added 9,800 square feet to the existing 23,800 square feet in the renovated historic Nishi Hongwanji Temple building and included the creation of the 198-seat Tateuchi Democracy Forum theater and the Democracy Lab.

The Democracy Center’s architecture responds to the scale and context of the Historic Building. Its metal exterior and glass curtain wall enables visibility between the Tateuchi Democracy Forum and the Norman Y. Mineta Democracy Plaza to create a sense of transparency and access that serves as a reminder that democracy is shaped through the involvement and engagement of individuals. The wedge-shaped Tateuchi Democracy Forum is designed for town hall meetings, lectures, discussions, and live performances. The wood-slatted ceiling was inspired by the original coffered ceiling of the temple building and traditional Japanese architecture.

Learn more about the Democracy Center’s upcoming events, programs, and partnerships at janm.org/democracy.

The Norman Y. Mineta Democracy Plaza

The Norman Y. Mineta Democracy Plaza connects JANM’s Pavilion, the Historic Building, and the Democracy Center together, creating a dynamic and inclusive campus that reflects the history, culture, and growth of the Japanese American community and Little Tokyo neighborhood. Once a through street, the Mineta Democracy Plaza was a site of forced removal for Americans of Japanese ancestry living in the area. Today it is a site of conscience, community, civic engagement, and social justice.

Secretary Norman Y. Mineta served on JANM’s board of governors from 1988 to 1995 and was the chair of the board of governors from 2010 to 2015. A trustee since 1996, he was the chair of the board of trustees from 2015 until his passing in May 2022. He and his family were forcibly removed from their home in San José, California, and incarcerated along with 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry for the duration of World War II. The family was initially held at the Santa Anita temporary detention center in Los Angeles, and then at the Heart Mountain concentration camp in Wyoming. Secretary Mineta represented his hometown of San José in the House of Representatives for over twenty years. The first Asian American appointed to a Presidential cabinet, he was named Secretary of Commerce under President Bill Clinton in 2000 and was named Secretary of Transportation by President George W. Bush in 2001. He was recognized with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian award, in 2006. In 2012 he was awarded JANM’s Distinguished Medal of Honor.

Omoide no Shotokyo (Remembering Old Little Tokyo)

The north side of First Street between Central Avenue and San Pedro Street, including the renovated former Buddhist temple building, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1995 to commemorate “the historical development of the Japanese American Community and symbolize the hardships and obstacles that this ethnic group has successfully overcome in securing its place in American society.”

In 1996, the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) of the City of Los Angeles executed a public art project entitled Omoide no Shotokyo (Remembering Old Little Tokyo) as part of the Little Tokyo Historical District Street Improvement Project. The art project began in 1990 when the CRA put out a request for proposals in order to “commemorate and describe the history of the development of the Little Tokyo Historic District.”

In 1991, the commission was awarded to Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, whose concept was to create six timelines in the sidewalk, beginning at the building line. Each timeline covers a decade from the 1890s to the 1940s. Near the entrances of the buildings, the timelines identify the businesses located there and the goods and services offered to the community. The sixth timeline is done in dark charcoal black and represents the 1940s when Japanese Americans were illegally forced from their homes and businesses by the U.S. government and incarcerated in concentration camps during World War II.

The installation also contains a second zone closer to the street with images and quotes from three generations of Japanese Americans who lived and/or worked in Little Tokyo. De Bretteville obtained the quotations by conducting more than 50 interviews and by reviewing books and old newspapers. She collaborated with Sonya Ishii, who submitted a proposal for the commission and whose work was recommended to de Bretteville to be part of the installation.

The red cement section contains drawings of wrappings or tsutsumi by Ishii (bamboo basket, wood crate, two-stack suitcase, detention packet, and cloth tied bundle (furoshiki)) and de Bretteville (trunk and envelope) that have served as containers for the community’s private and public memories. De Bretteville also added an apple pie to the collection of drawings in response to the comment from one informant, who identified himself “as American as apple pie.”

The installation also incorporates the work of Nobuho Nagasawa, who proposed creating a sculpture of a camera used by Japanese American photographer Toyo Miyatake. Miyatake, who opened his Little Tokyo studio in 1923, smuggled a lens and a film holder into the Manzanar concentration camp where he and his family were forced to live during the war. He had a camera built and secretly documented their lives in camp when cameras were considered contraband.

Nagasawa created a bronze replica of that camera that was three times as large as the original. First installed in 1993 on First Street, the sculpture originally had a slide projector inside that projected images that Miyatake shot in Manzanar. The sculpture was moved into JANM’s plaza, facing one of the windows of the Historic Building, where Miyatake’s photographs are screened.

De Bretteville described her project as an attempt “to invent various ways for the contradictory multiple identities and complex generational different subjectivities to be represented. Thus, the apple pie forces people to ask why it is there. It is the only image that could not be across the street in the Japanese created side of Little Tokyo and truly belongs in the Old Little Tokyo representation.”

Omoide no Shotokyo spans the Little Tokyo Historic District, from the north end of JANM’s Historic Building to Judge John Aiso Street and the old Union Church building (now the Union Center for the Arts). The title of the work appears in Japanese kanji characters at both ends of the Historic District.

OOMO Cube

The OOMO Cube by photographic messaging artist Nicole Maloney was installed near the main entrance of the JANM Pavilion in 2014. OOMO stands for “Out Of Many One” and Maloney conceived of her installation as a giant Rubik’s cube with five sides filled with photographs and the sixth side as a mirror.

Maloney explained that people are often identified through five different characteristics: race, religion, gender, socio-economic status, and sexual orientation. The cube allows visitors to JANM to have interactions with it by rotating the sections into different configurations. Maloney hoped that those interacting with her cube will be reminded that everyone belongs to one world and one humanity and that it will encourage people to “stand in awe instead of judgment of one another.”

The installation was made possible by OneWest Bank, the City of Los Angeles, Claremont Lincoln University, and JANM.

Moon Beholders Mural

In 2014, JANM commissioned a mural on the north wall of the Tateuchi Democracy Forum. Muralist, author, and illustrator Katie Yamasaki earned the commission and produced Moon Beholders. It was approved by the Los Angeles Cultural Affairs Commission and the City of Los Angeles Public Art Committee.

The mural is intended to represent, celebrate, challenge, and preserve different concepts within the Japanese American culture, both contemporary and historic, while connecting with the diverse community around JANM. The mural depicts a young girl, clothed in several furoshiki, a traditional Japanese cloth often used to carry, cover, and protect objects, most often gifts.

The mural also depicts lanterns or akari, representing light or illumination and displays a haiku poem by Basho, a famous Japanese poet from the Edo period. JANM organized a community day to gather interested individuals to help paint the bottom half of the mural under Yamasaki’s direction.

Yamasaki is based in Brooklyn, New York and has painted over 60 murals around the world. She also has published a number of books, including Fish for Jimmy, which she wrote and illustrated.

Watch a behind-the-scenes look at Katie Yamasaki’s Moon Beholders. WATCH NOW