Online Exhibition

Artwork

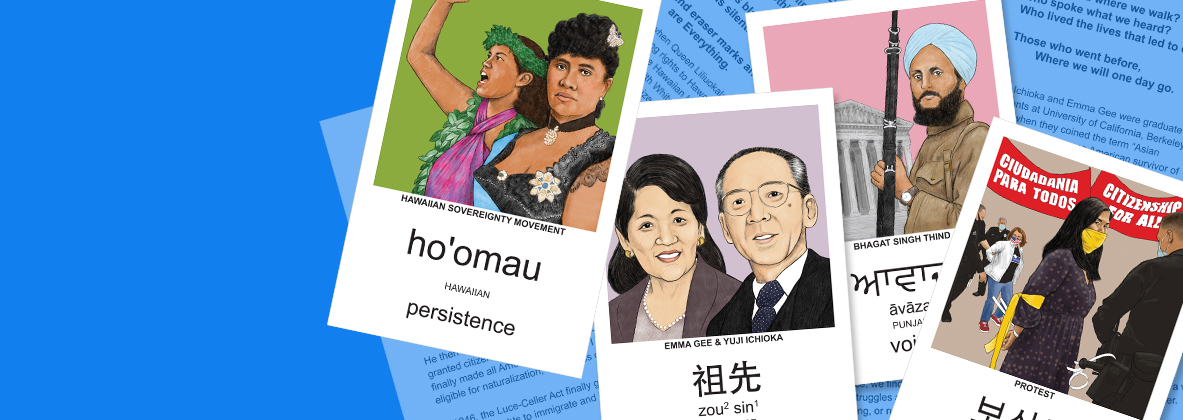

An American Vocabulary: Words to Action consists of twenty-one multilingual flash cards that illustrate the four themes of ancestor, voice, persistence, and care through the portrayal of Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander (AANHPI) figures, events, actions, and values. A set of discussion questions invites people to consider their own relationships to language, identity, and community. The flash cards symbolize the way AANHPI communities translate their inimitable American histories across linguistic, cultural, and imaginative barriers.

We invite you to use these cards to expand and explore your own imagination of history and our present realities. View the card images below.

Flash card decks are available at the JANM Store. Buy Now

Artwork

Ongoing

Artwork

An American Vocabulary: Words to Action consists of twenty-one multilingual flash cards that illustrate the four themes of ancestor, voice, persistence, and care through the portrayal of Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander (AANHPI) figures, events, actions, and values. A set of discussion questions invites people to consider their own relationships to language, identity, and community. The flash cards symbolize the way AANHPI communities translate their inimitable American histories across linguistic, cultural, and imaginative barriers.

We invite you to use these cards to expand and explore your own imagination of history and our present realities. View the card images below.

Flash card decks are available at the JANM Store. Buy Now

Artwork

Ongoing

Artwork

An American Vocabulary: Words to Action consists of twenty-one multilingual flash cards that illustrate the four themes of ancestor, voice, persistence, and care through the portrayal of Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander (AANHPI) figures, events, actions, and values. A set of discussion questions invites people to consider their own relationships to language, identity, and community. The flash cards symbolize the way AANHPI communities translate their inimitable American histories across linguistic, cultural, and imaginative barriers.

We invite you to use these cards to expand and explore your own imagination of history and our present realities. View the card images below.

Flash card decks are available at the JANM Store. Buy Now

Ancestor

Who’s a community ancestor that has inspired you?

What in their life and legacy resonates with you?

Who walked where we walk?

Who spoke what we heard?

Who lived the lives that led to ours?

Those who went before,

Where we will one day go.

Emma Gee & Yuji Ichioka

Yuji Ichioka and Emma Gee were graduate students at University of California, Berkeley in 1968 when they coined the term “Asian American.” A Japanese American survivor of World War II incarceration and a Chinese American passionate about racial equality, they gathered Asian students in their home to imagine how their communities could fight for justice alongside others.

To start, their group discarded the term “Oriental,” with its racist connotations, for a new, self-chosen designation: “Asian American.”

Emma Gee & Yuji Ichioka

Yuji Ichioka and Emma Gee were graduate students at University of California, Berkeley in 1968 when they coined the term “Asian American.” A Japanese American survivor of World War II incarceration and a Chinese American passionate about racial equality, they gathered Asian students in their home to imagine how their communities could fight for justice alongside others.

To start, their group discarded the term “Oriental,” with its racist connotations, for a new, self-chosen designation: “Asian American.”

Christina Yuna Lee

Christina Yuna Lee was a Korean American woman. She loved visual art and music, and was known as a kind and thoughtful coworker. Passionate about racism and justice, she would talk for hours with friends about the role of Asians in the music industry.

On February 13, 2022, she was killed in her New York City apartment by a man who followed her into her building. Prosecutors did not investigate her murder as a hate crime.

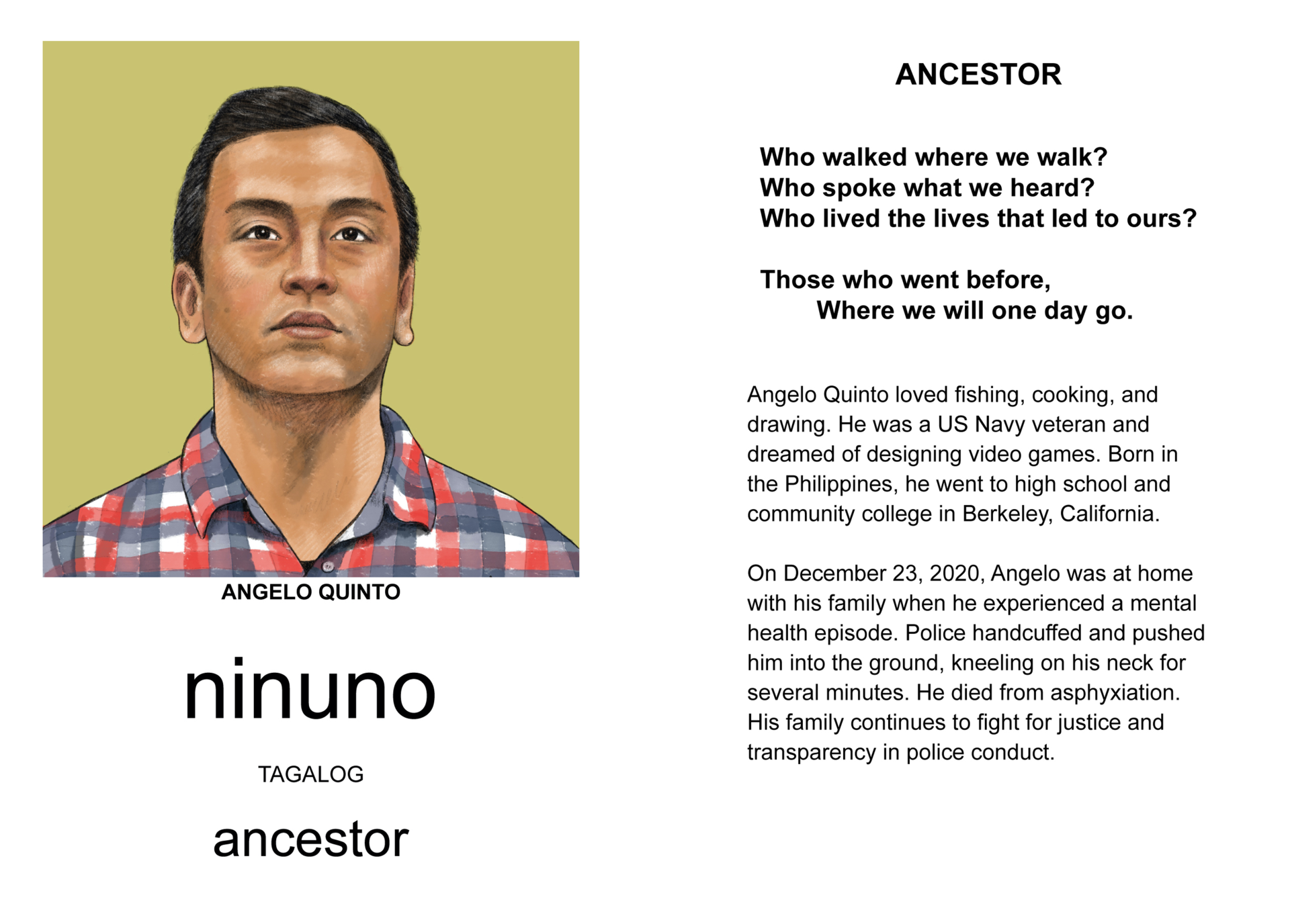

Angelo Quinto

Angelo Quinto loved fishing, cooking, and drawing. He was a US Navy veteran and dreamed of designing video games. Born in the Philippines, he went to high school and community college in Berkeley, California.

On December 23, 2020, Angelo was at home with his family when he experienced a mental health episode. Police handcuffed and pushed him into the ground, kneeling on his neck for several minutes. He died from asphyxiation. His family continues to fight for justice and transparency in police conduct.

Kawen Toagamau Segaula Young

Ms. Kawen Toagamau Segaula Young was a Samoan American leader. A living “encyclopedia of protocols and policymaking,” she used her experience as a lifelong public service to connect Pacific Islander communities with inaccessible infrastructure and government resources.

From speaking with the president and lawmakers to personally rallying volunteers, Kawen’s work spanned public health, immigration, data disaggregation, and redistricting. Even during her final days in the hospital, she was calling in to redistricting meetings, fighting for fair political representation for her beloved communities.

Voice

How do you communicate your values to the world around you?

What forms of creativity and activism speak most strongly to you?

shout, scream, sing, pray

dance, draw, dream, whisper

move, march, make, laugh

Pour yourself into the world

Fierce and kind and brilliant

Bhagat Singh Thind

Bhagat Singh Thind was a Sikh American. After college, he was recruited by the US Army to fight in World War I. Postwar, his promised US citizenship was revoked because he was not White.

He then battled in court for two decades to be granted citizenship. In 1935, the Nye-Lea Act finally made all American World War I veterans eligible for naturalization, regardless of race.

In 1946, the Luce-Celler Act finally granted all Indians the rights to immigrate and become US citizens.

The Linda Lindas

The Linda Lindas are a four-member punk band from Los Angeles. Eloise Wong, Lucia and Mila de la Garza, and Bela Salazar make music about their experiences and perspectives as young Asian and Latinx women.

Their songs, including “Racist, Sexist Boy,” tap into a long tradition of punk music speaking out on social issues and injustices. Since going viral in 2021, they've signed to legendary punk label Epitaph, released their debut album, and brought their music to stages around the world.

Larry Itliong

Larry Itliong was a Filipino American man, a husband, brother, and father. He loved smoking cigars and playing cards. He came to the US as a teenager and found work as a migrant laborer.

For over five decades, Larry was one of the country’s preeminent labor organizers. He led the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee and co-founded the United Farm Workers (UFW) with Cesar Chavez. He later left the UFW over concerns with the poor treatment of aging Filipino workers.

Yellow Pearl

And time is telling, only how long it takes

Layer after layer, as our beauty unfolds

Until our captor we’ll hold in peril

—Yellow Pearl, “A Grain of Sand”

Yellow Pearl (Nobuko Miyamoto, Chris Iijima, Charlie Chin) was an Asian American folk music trio founded in 1970. Raised in families who’d experienced incarceration, bullying, and racism, their music soundtracked the early Asian American movement. In the midst of national upheaval and protest, they created intentionally political and distinctly Asian American songs targeting inequality, racism, and sexism.

Yellow Rage

Yellow Rage is an Asian American spoken word duo. Korean and Lao American poets Michelle Myers and Catzie Vilayphonh met at Philadelphia’s Asian Arts Initiative. They competed in Def Poetry Slam (2000), and were featured in HBO’s Def Poetry Jam (2001), a show that introduced slam poetry to mainstream audiences.

The first Asian American women on this national platform, Michelle and Catzie were boldly anti-racist, anti-sexist, and empowering voices. Both continue to write and educate new generations of young artists of color.

Yellow Rage

Yellow Rage is an Asian American spoken word duo. Korean and Lao American poets Michelle Myers and Catzie Vilayphonh met at Philadelphia’s Asian Arts Initiative. They competed in Def Poetry Slam (2000), and were featured in HBO’s Def Poetry Jam (2001), a show that introduced slam poetry to mainstream audiences.

The first Asian American women on this national platform, Michelle and Catzie were boldly anti-racist, anti-sexist, and empowering voices. Both continue to write and educate new generations of young artists of color.

Persistence

What’s a part of your community’s history that you want remembered and recognized?

What do you see that’s at risk of being erased from public memory?

When you hear nothing, listen.

When you see nothing, look.

No canvas is blank,

No room is silent.

Behind eraser marks and echoes

are Everything.

Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement

In 1893, when Queen Liliuokalani tried to restore voting rights to Hawaiian and Asian subjects of the Hawaiian Kingdom, US armed forces joined with White elitists in Hawai‘i to overthrow and seize control of the Kingdom. Five years later, despite protests by the Queen and Hawaiian nationals, the rebels, in cahoots with the US and without a proper treaty, staged a fake annexation, handing the Hawaiian Islands over to the US.

In 1993, Congress apologized for the wrongful taking, but did nothing to undo the illegal annexation and 124 years of occupation and plundering. The Hawaiian independence movement continues.

Movement for Redress & Reparations

During World War II, over 120,000 Japanese, including 80,000+ American citizens, were removed from their homes and businesses by armed soldiers. For years, they lived in desert concentration camps before returning to restart their lives from scratch.

In the 1970s, a chorus of Japanese American organizers, community organizations, and politicians began to demand redress. From public gatherings to Congressional hearings, they spoke up to ensure their families’ experiences would not be erased. In 1988, the Civil Liberties Act finally provided an official apology and reparations to each surviving incarceree.

Stop ICE

In the 1960s and ’70s, the US recruited Southeast Asians as wartime allies. As the US withdrew, they promised safe passage to Vietnamese, Lao, Hmong, Mienh, Khmer, and others, the largest refugee resettlement in US history.

Arriving refugees were placed in impoverished areas and given little support. Many were driven to criminal activities that later targeted them for deportation. Since 1998, over 16,000 Southeast Asian Americans have received deportation orders, many of whom arrived in this country as young children.

Thai Garment Workers

On August 2, 1995, seventy-two Thai garment workers were rescued from slavery in El Monte, California. They had been trafficked from Thailand with false promises of legal work and held under threats of violence.

After being freed by government agencies and the Thai Community Development Center, the workers were detained by US Immigration. Immigrants’ rights organizations lobbied for nine days before they were finally released into the care of the Thai CDC. They were later granted US residency, reunited with their families, and won a settlement from the corporations that profited from their enslavement.

Chinese Massacre of 1871

The largest recorded mass lynching in American history took place on October 25, 1871, in Los Angeles’s Chinatown. After a policeman and civilian were killed in a dispute between Chinese gangs, a 500-person mob formed on the borders of Chinatown.

They trapped Chinese in the neighborhood before entering to shoot and torture. Nineteen Chinese were killed, including a medical doctor and a fourteen-year-old boy. Eight of the lynchers were convicted of manslaughter. Their sentences were later overturned.

Care

What are some ways you’ve offered and received care?

Imagine a society rooted in care—what would it look, sound, and feel like?

When the winds come

We kindle warmth where we can

Build fires and homes and friends

We plant on land we do not own.

Giving care, taking care,

Feeding each other.

Protest

Protest is a way to show public support for each other.

When our friends and communities experience injustice, we find ways to draw attention to their struggles and issues. Whether marching, picketing, or running letter-writing and social media campaigns, acts of protest remind people that they are not alone. It also sends a message to powerful institutions and authorities that we will not let them harm or ignore our community members.

Solidarity

Solidarity is a way of viewing our world as fundamentally connected. People and communities don’t struggle or succeed alone, but alongside those around us. Everyone benefits when oppressive policies and systems are changed or overthrown.

Tsuru for Solidarity is a nonviolent, direct action project of Japanese American social justice advocates and allies working to end detention sites and support directly impacted immigrant and refugee communities that are being targeted by racist, inhumane immigration policies.

Mutual Aid

Mutual aid is a way for us to take care of each other. When society fails to provide for our neighbors’ needs, we work together to provide what may be lacking: food, clothing, housing, legal services, education, and more.

This starts with shifting our perceptions of others and the world around us. We stop striving against each other for status and limited resources, and instead choose to be generous and compassionate. We see each other as human beings worthy of compassion. We flourish by building strong networks of care and human dignity.

Radical Hospitality

Food can be nourishment, culture, history, and hospitality all in one. Oakland’s People’s Kitchen Collective (PKC) is a food-centered political education project. Valuing “radical hospitality,” they create immersive experiences honoring the shared struggles of their people and addressing urgent social issues.

Feasts of resistance are another way to blend food with compassion. Popularized by activist Tony Osumi, participants share a meal tying dishes to socially significant discussion. Chef-activist Sean Liu (MSG Kitchen) pairs a beet salad with a talk about the 1903 Oxnard Sugar Beets Strike.

Support for Elders

Many AANHPI elders face particular challenges, including language barriers, immigration issues, poverty, and more.

There are many ways to support our elders. We can distribute resources like masks, sanitary supplies, and food. We can volunteer to assist them with daily tasks like shopping for groceries, translating or paying bills, and providing rides and safety patrols. And we can support their voices, amplifying their concerns to politicians, landlords, and other community stakeholders.

Support the understanding and appreciation of the Japanese American experience.