Wakaji Matsumoto was born to Wakamatsu and Haru (née Motoyama) Motoyama on July 17, 1889, in Jigozen, Saiki-gun (now Hatsukaichi-shi), Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. Wakamatsu was a fisherman by trade but he also farmed a small plot of land adjacent to his home. As the youngest son, he knew that his prospects for success were limited in Japan because he was unable to inherit the family business, so he responded to a Japanese newspaper advertisement seeking workers for the pineapple and sugar beet fields in Hawai‘i. In 1890, Wakamatsu and Haru left Wakaji and his older sister, Matsu, with relatives in Japan to work as contract laborers on Kauai. They were among the nearly 30,000 workers from the Hiroshima area that left Japan for Hawai‘i.

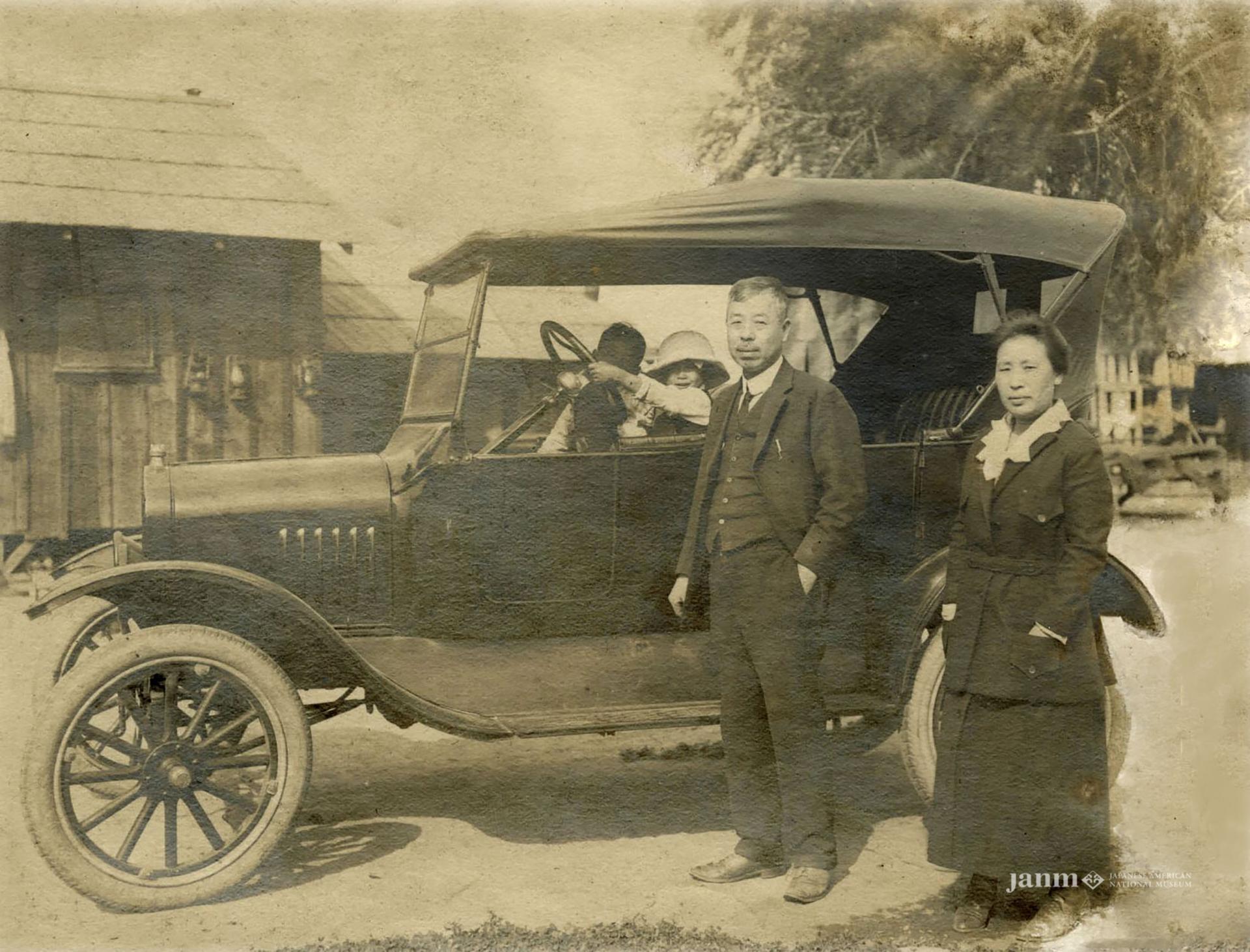

Wakamatsu and Haru had two children in Hawai‘i. When their backbreaking work in the fields did not yield a better future for their family, Wakamatsu sought his fortune on the West Coast. Having completed their labor contract, Wakamatsu sent Haru and the children to Jigozen and moved to Los Angeles to become a farmer. Wakamatsu operated two farms in present-day Maywood and Laguna, now known as the City of Commerce. In 1906, he sent for Wakaji to join him in the United States.

Like many young Japanese men, Wakaji traveled by ship from Japan to Victoria, British Columbia, and from there by boat and train to Los Angeles. He was seventeen when he reunited with Wakamatsu—whom he hardly knew. Although he worked in the fields and drove produce to the Los Angeles 7th Street Market, he really wanted to become a graphic artist—a challenging undertaking in a new world and one that was discouraged by Wakamatsu. Luckily, Wakaji’s future wife and picture bride, Tei Kimura, would eventually manage the family business.

Wakaji and Tei married in 1912, an arrangement made by Tei’s older brother, who was Wakaji’s friend. A descendant of a samurai family, Tei found herself in a foreign world when she arrived on the farm, but Wakamatsu took her under his wing and taught her how to manage it. With the family business in good hands, Wakamatsu returned to Jigozen in 1917 and Wakaji began to pursue art and photography as his profession.

Wakaji took a correspondence course in photography and knew that he wanted to become a professional photographer. While Tei ran the family farm, he moved to San Diego to develop his craft and advance his studies in photography. During that time he may have studied under Masashi Shimotsusa, who ran a photography studio and school and was skilled at creating panoramic photographs. By 1922, Wakaji was an active photographer in the Los Angeles photography community. By 1925, he was an assistant at Toyo Miyatake’s studio, Toyo Studio LA, and a member of the Japanese Camera Pictorialists of California. He also produced panoramas of Japanese American tenant farmers in Los Angeles and other photographs as a form of personal expression.

During this time, Wakaji and Tei weighed the challenges of farming in Southern California versus the benefits of returning to Japan. Although their children received a good education in Los Angeles, the Matsumotos preferred that they receive a Japanese education. Wakaji also wanted to return to Japan to open his own photography studio. The Matsumotos’ desire to see their children educated in Japan combined with two years of crop failure, inability to own land, and competition to establish a photography studio in Los Angeles, drove their decision to return to Hiroshima in the summer of 1927.

Wakaji opened Hiroshima Shashinkan (Hiroshima Photography Studio) in the Naka Ward, near the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall—now known as the Atomic Bomb Dome. His family lived above the studio. A skilled photographer, he had the advantage of using camera equipment not yet available in Japan because he bought the latest equipment in the US with earnings from the family farm. He did studio work, commercial photography, and worked as contract photographer for the Japanese military and other businesses in the area. His work was highly regarded and his services were in high demand. He also took photographs of daily life in Hiroshima City and the surrounding countryside. Many of those photographs are the only record of people, events, and locations that were later destroyed by the atomic bomb.

In 1942, Wakaji closed his studio because he was unable to secure photography supplies and moved his family to his parents’ home in Jigozen. In 1943, he was drafted to work in a coal mine in Ube-shi, Yamaguchi Prefecture, where he developed a serious lung disease that plagued him for the rest of his life. He returned home and resumed his photography in the small studio that he created at his parents’ home. In 1945, a stray American bomb destoyed their neighbor’s home and Wakaji’s studio. Luckily, no one was injured in the Wakaji household and all of Wakaji’s photographs were stored safely away from his studio.

Wakaji passed away in Jigozen in 1965. He was seventy-six years old. Tei continued to live in the family home for another thirty years. She passed away in 1995 at 101 years old. Wakaji’s boxes of negatives and photographs remained undisturbed until they were discovered by Hitoshi Ohuchi, their grandson and a photographer himself, in 2008. Upon recognizing their value, he arranged for them to be placed with the Hiroshima City Archives. Wakaji’s photographs of Hiroshima before the atomic bomb have great historical significance. His collection increased the total number of existing photographs of Hiroshima ten-fold, as most were destroyed by the bomb in 1945.