Online Exhibition

Wakaji Matsumoto

Hiroshima

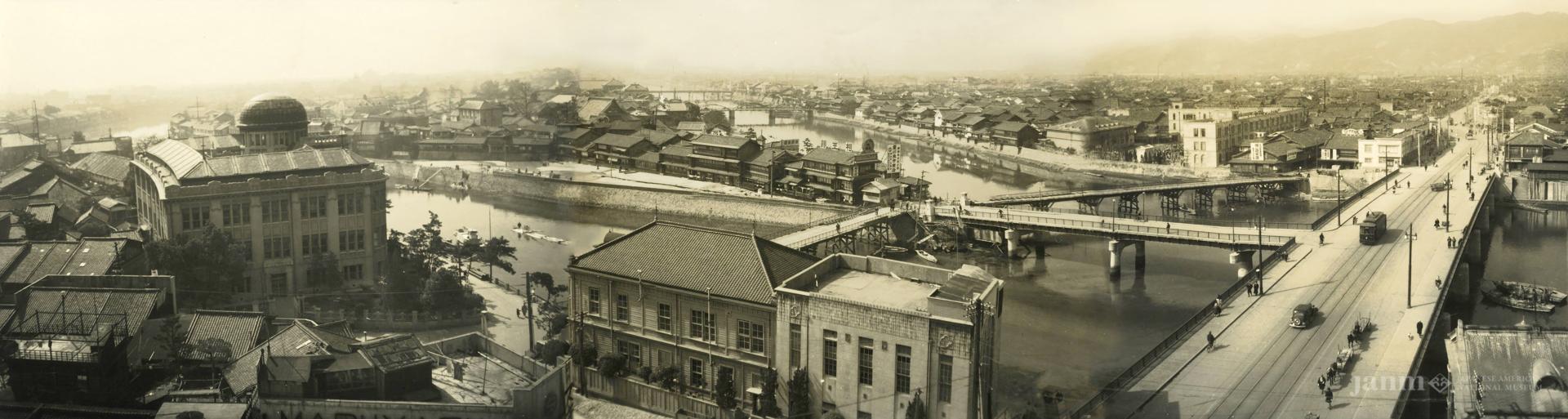

The Matsumoto family returned to Hiroshima in the summer of 1927. Upon their return, Wakaji opened Hiroshima Shashinkan (Hiroshima Photography Studio) in the Naka Ward, near the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall—now known as the Atomic Bomb Dome. The Matsumotos lived above the studio.

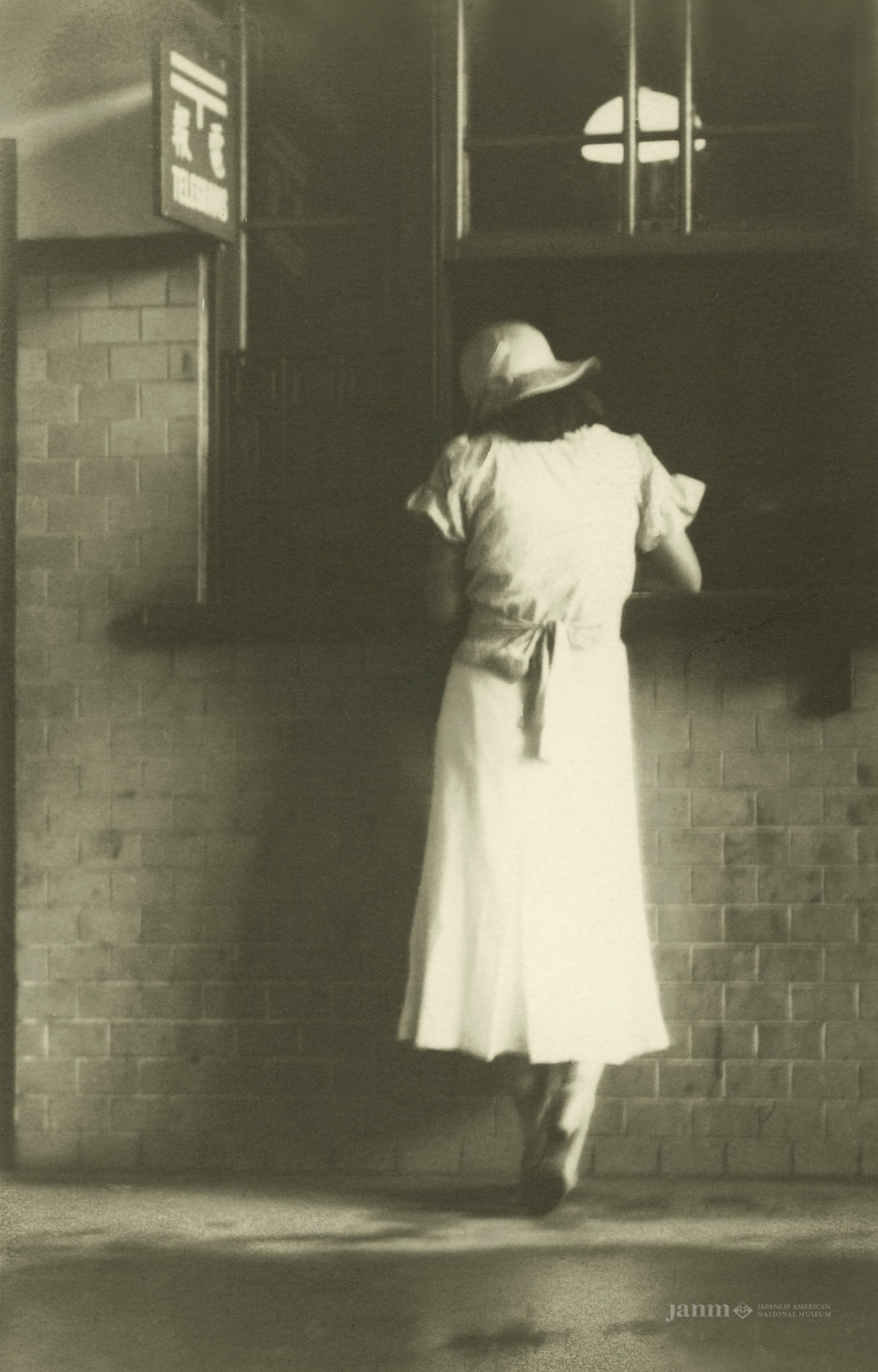

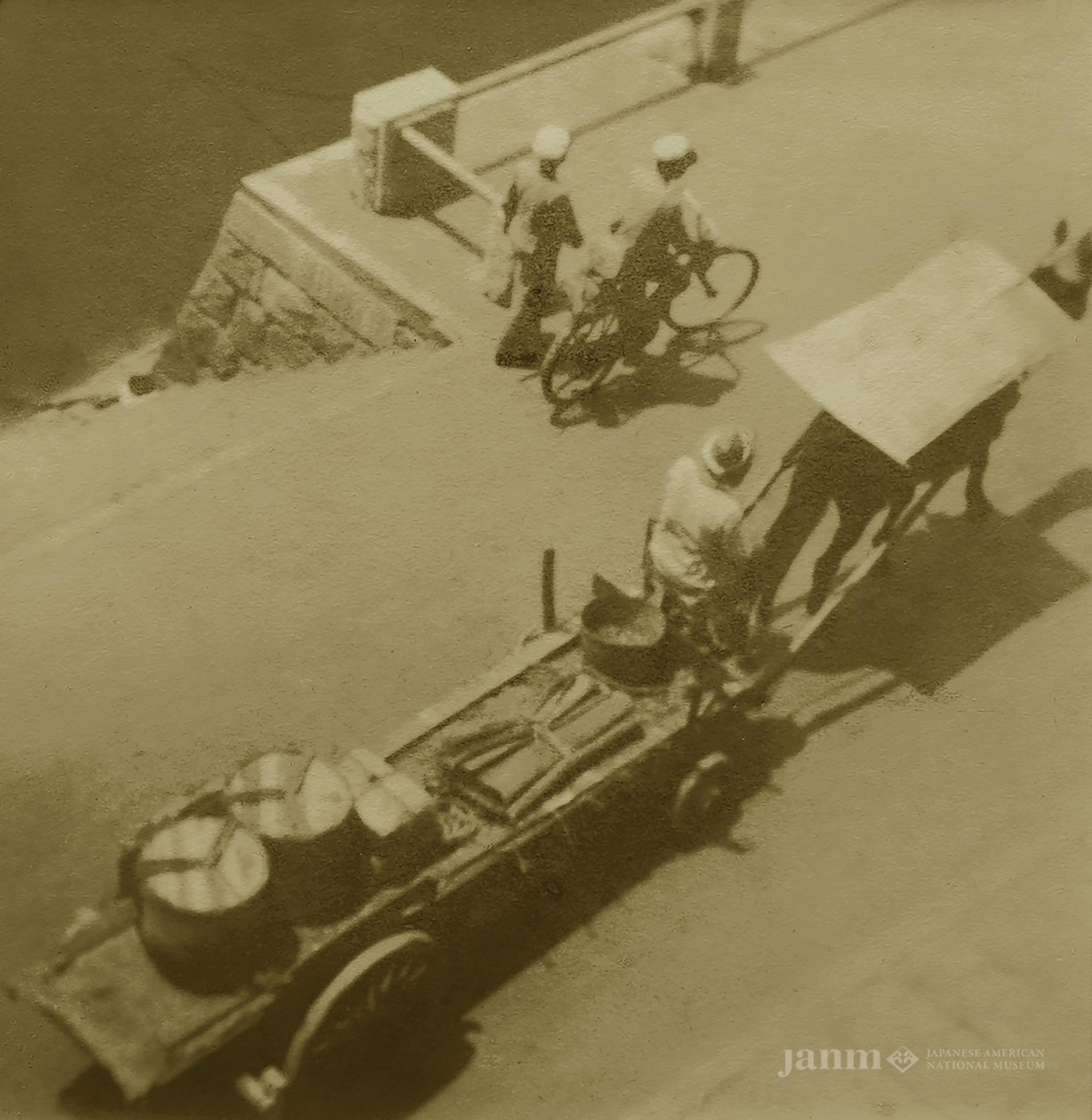

Wakaji did studio work, commercial photography, and contract photography for the Japanese military and other businesses in the area. His work was highly regarded and his services were in high demand. He also took photographs of daily life in Hiroshima City and the surrounding countryside. Many of those photographs are the only record of people, events, and locations that were later destroyed by the atomic bomb.

By 1929, Hiroshima was bustling with 270,000 people and was one of the educational, cultural, political, and economic centers of Japan. During the 1920s, Japan began to develop a deeper appreciation for photography to present narratives and record Japanese society and culture. By the late 1920s, avant-garde styles in Europe like Surrealism, New Objectivity, and Bauhaus were available in Japanese books and magazines and abundant in Wakaji’s work which blended art with documentation. Wakaji’s interest in a documentary approach to photography was encouraged by the trends of the late 1920s and early 1930s. His photographs during this period are personal, intimate memorials to a city with a tragic fate.

When Japan entered World War II, the country’s resources were devoted to military purposes. Wakaji eventually closed his studio because he was unable to secure his supplies. He moved his family to his parents’ home in Jigozen. In 1945, a stray American bomb destoyed their neighbor’s home and Wakaji’s studio. Luckily, no one was injured in the Wakaji household and all of Wakaji’s photographs were stored safely away from his studio.

After the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, Wakaji and Tei wheeled a cart into the city to look for relatives near the former studio, which had been obliterated. They found Tei’s cousin and laid him into the cart to transport him back home but he died before they reached Jigozen.

Wakaji passed away at seventy-six years old in 1965. Tei continued to live in the family home for thirty years and passed away at 101 years old in 1995. Wakaji’s photographs remained undisturbed until they were discovered by Wakaji and Tei’s grandson, Hitoshi Ohuchi, in 2008. Upon recognizing their value, he placed them in the Hiroshima City Archives. The discovery of Wakaji’s photographs of Hiroshima before the bomb had enormous historic significance, as his collection increased the total number of existing photographs of Hiroshima ten-fold, most existing photographs having been destroyed by the 1945 atomic bomb.

Watch the video to learn more about Wajaki’s life in Hiroshima and explore his body of work in the two photo galleries below.

Hiroshima

Ongoing

Hiroshima

The Matsumoto family returned to Hiroshima in the summer of 1927. Upon their return, Wakaji opened Hiroshima Shashinkan (Hiroshima Photography Studio) in the Naka Ward, near the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall—now known as the Atomic Bomb Dome. The Matsumotos lived above the studio.

Wakaji did studio work, commercial photography, and contract photography for the Japanese military and other businesses in the area. His work was highly regarded and his services were in high demand. He also took photographs of daily life in Hiroshima City and the surrounding countryside. Many of those photographs are the only record of people, events, and locations that were later destroyed by the atomic bomb.

By 1929, Hiroshima was bustling with 270,000 people and was one of the educational, cultural, political, and economic centers of Japan. During the 1920s, Japan began to develop a deeper appreciation for photography to present narratives and record Japanese society and culture. By the late 1920s, avant-garde styles in Europe like Surrealism, New Objectivity, and Bauhaus were available in Japanese books and magazines and abundant in Wakaji’s work which blended art with documentation. Wakaji’s interest in a documentary approach to photography was encouraged by the trends of the late 1920s and early 1930s. His photographs during this period are personal, intimate memorials to a city with a tragic fate.

When Japan entered World War II, the country’s resources were devoted to military purposes. Wakaji eventually closed his studio because he was unable to secure his supplies. He moved his family to his parents’ home in Jigozen. In 1945, a stray American bomb destoyed their neighbor’s home and Wakaji’s studio. Luckily, no one was injured in the Wakaji household and all of Wakaji’s photographs were stored safely away from his studio.

After the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, Wakaji and Tei wheeled a cart into the city to look for relatives near the former studio, which had been obliterated. They found Tei’s cousin and laid him into the cart to transport him back home but he died before they reached Jigozen.

Wakaji passed away at seventy-six years old in 1965. Tei continued to live in the family home for thirty years and passed away at 101 years old in 1995. Wakaji’s photographs remained undisturbed until they were discovered by Wakaji and Tei’s grandson, Hitoshi Ohuchi, in 2008. Upon recognizing their value, he placed them in the Hiroshima City Archives. The discovery of Wakaji’s photographs of Hiroshima before the bomb had enormous historic significance, as his collection increased the total number of existing photographs of Hiroshima ten-fold, most existing photographs having been destroyed by the 1945 atomic bomb.

Watch the video to learn more about Wajaki’s life in Hiroshima and explore his body of work in the two photo galleries below.

This project was made possible with support from California Humanities, a non-profit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Visit calhum.org.

Media Sponsor: ![]()

To inquire about re-use of these photos, please contact collections@janm.org.

Hiroshima

Ongoing

Hiroshima

The Matsumoto family returned to Hiroshima in the summer of 1927. Upon their return, Wakaji opened Hiroshima Shashinkan (Hiroshima Photography Studio) in the Naka Ward, near the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall—now known as the Atomic Bomb Dome. The Matsumotos lived above the studio.

Wakaji did studio work, commercial photography, and contract photography for the Japanese military and other businesses in the area. His work was highly regarded and his services were in high demand. He also took photographs of daily life in Hiroshima City and the surrounding countryside. Many of those photographs are the only record of people, events, and locations that were later destroyed by the atomic bomb.

By 1929, Hiroshima was bustling with 270,000 people and was one of the educational, cultural, political, and economic centers of Japan. During the 1920s, Japan began to develop a deeper appreciation for photography to present narratives and record Japanese society and culture. By the late 1920s, avant-garde styles in Europe like Surrealism, New Objectivity, and Bauhaus were available in Japanese books and magazines and abundant in Wakaji’s work which blended art with documentation. Wakaji’s interest in a documentary approach to photography was encouraged by the trends of the late 1920s and early 1930s. His photographs during this period are personal, intimate memorials to a city with a tragic fate.

When Japan entered World War II, the country’s resources were devoted to military purposes. Wakaji eventually closed his studio because he was unable to secure his supplies. He moved his family to his parents’ home in Jigozen. In 1945, a stray American bomb destoyed their neighbor’s home and Wakaji’s studio. Luckily, no one was injured in the Wakaji household and all of Wakaji’s photographs were stored safely away from his studio.

After the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, Wakaji and Tei wheeled a cart into the city to look for relatives near the former studio, which had been obliterated. They found Tei’s cousin and laid him into the cart to transport him back home but he died before they reached Jigozen.

Wakaji passed away at seventy-six years old in 1965. Tei continued to live in the family home for thirty years and passed away at 101 years old in 1995. Wakaji’s photographs remained undisturbed until they were discovered by Wakaji and Tei’s grandson, Hitoshi Ohuchi, in 2008. Upon recognizing their value, he placed them in the Hiroshima City Archives. The discovery of Wakaji’s photographs of Hiroshima before the bomb had enormous historic significance, as his collection increased the total number of existing photographs of Hiroshima ten-fold, most existing photographs having been destroyed by the 1945 atomic bomb.

Watch the video to learn more about Wajaki’s life in Hiroshima and explore his body of work in the two photo galleries below.

This project was made possible with support from California Humanities, a non-profit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Visit calhum.org.

Media Sponsor: ![]()

To inquire about re-use of these photos, please contact collections@janm.org.

Wakaji Matsumoto—Episode 3: Hiroshima

Hiroshima: Its People and Environs

Explore pre-war Hiroshima through Wakaji’s artistic lens.

Click “Gallery View” to view the photographs and captions in full frame. Click on the magnifying glass to use our extended zoom feature.

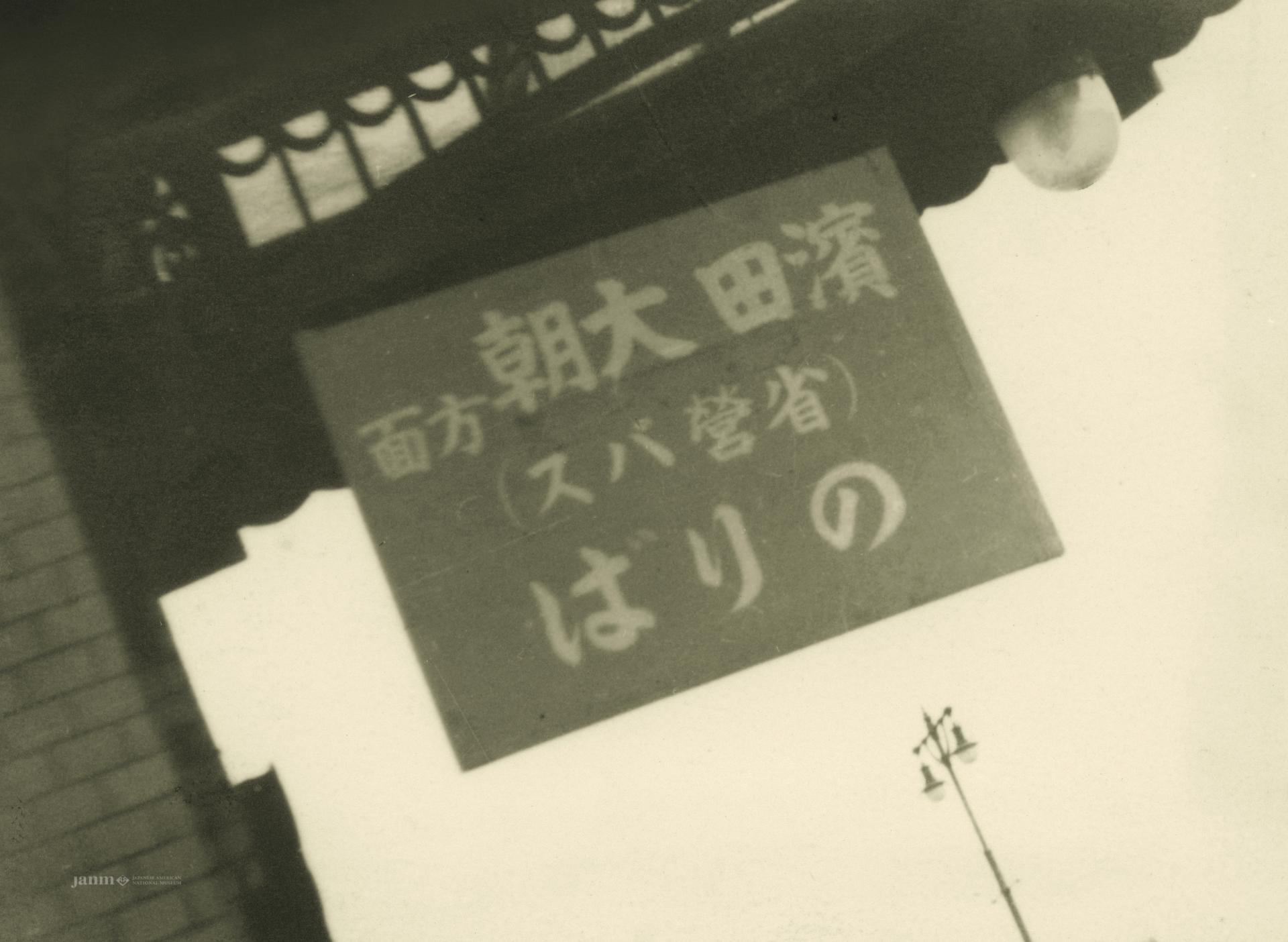

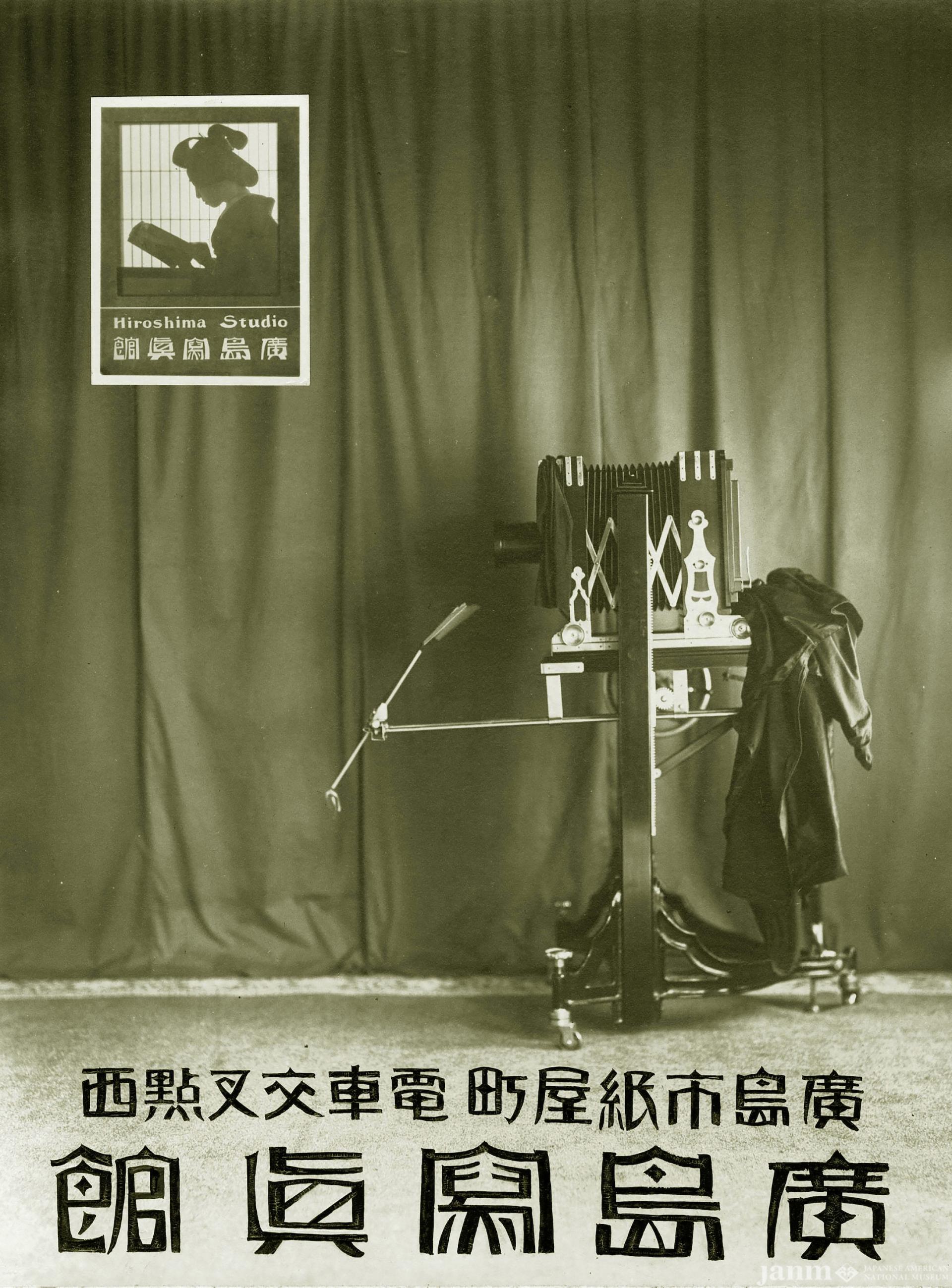

Hiroshima Studio Label

Commercial label for Hiroshima Studio, “Hiroshima Shashinkan”

Wakaji’s Photo Studio, Hiroshima Shashinkan

Wakaji’s photo studio, Hiroshima Shashinkan, was located approximately 2-1/2 blocks from the hypocenter of the atomic bomb. The studio and surrounding environs were completely destroyed by the bomb blast. A small interpretive sign indicates the location of Wakaji’s studio, which is currently the site of Sogo Department Store.

Hiroshima Studio Advertisement

Logo superimposed over his camera set up was created by Wakaji Matsumoto to advertise the Hiroshima Shashinkan photo studio. The geisha logo was also used on his stationery and invoices.

Wakaji and Hiroshima Camera Club

Wakaji (center left front) with the Hiroshima Koga Club, 1935. The word “koga” means “photograph” and was a term commonly used prior to WWII. The club members went on field trips to photograph various locations in and around Hiroshima.

PANORAMIC PHOTOS

Uncover details of Hiroshima through Wakaji’s panoramic photographs.

Click “Gallery View” to view the photographs and captions in full frame. Click on the magnifying glass to use our extended zoom feature.

Elementary School Athletic Event

Athletic event at Jigozen Elementary School, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima Prefecture

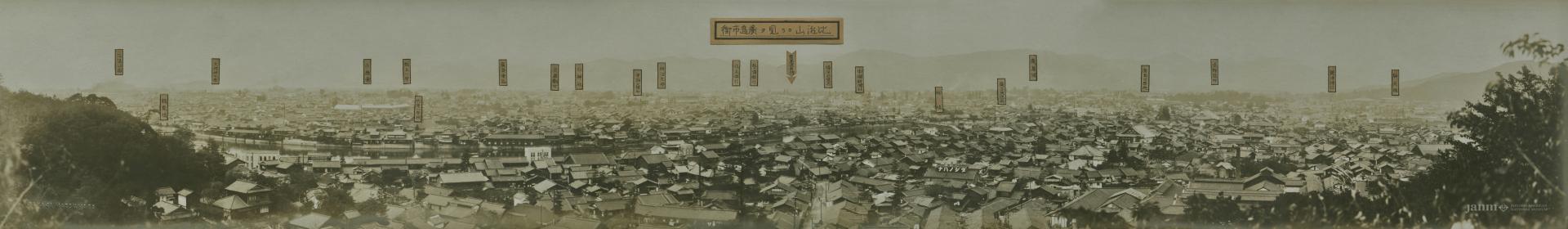

View of Central Hiroshima, Naka Ward, looking east

Hiroshima Castle and Japan Broadcasting Station are to the left of the Hiroshima Girls Academy (4th marker from right).