Tenacious and prolific, Japanese American artist Miné Okubo continued perfecting her art even as war intervened twice during the nascent years of her promising career.

A native of Riverside, Calif., Okubo is acclaimed for Citizen 13660, a book of her 198 drawings revealing life inside a temporary Bay Area detention center and a Utah concentration camp where she was incarcerated with thousands of other Japanese during World War II. It is the first book about the American concentration camp experience by a former prisoner.

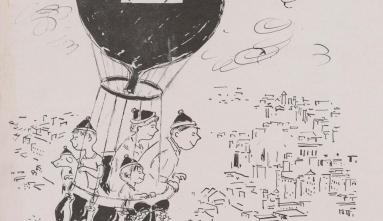

In JANM’s exhibition, Miné Okubo’s Masterpiece: The Art of Citizen 13660, Okubo’s expressive vignettes document the camp’s spartan conditions of crammed barracks, perennial long lines, and harsh weather. She also reveals the dejection, resentment, and frequent boredom that engulfed incarcerees.

Okubo is no mere observer of incarceration. She is Citizen 13660, the government-assigned number for her family, and her illustrations portray a citizenship in turmoil.

Born in 1912, Okubo’s parents were from Japan; her father was a scholar, and her mother was trained as a calligrapher. Her father found work as a gardener, but her mother raised six children, limiting her pursuit of art. This deepened Okubo’s determination as an artist, vowing not to marry, or to “wash someone else’s socks.”

Okubo earned a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Art at the University of California, Berkeley. She won a prestigious Bertha Henicke Taussig traveling arts fellowship in 1938 that included studying with Cubist artist Fernand Léger in Paris. But war in Germany disrupted her European travels, and after learning her mother was ill, Okubo returned home.

In San Francisco, she painted murals under the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Arts Project. On one Bay Area project, she worked alongside famed Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.

After the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, U.S. Executive Order 9066 led to West Coast families of Japanese descent to be incarcerated at remote American concentration camps. Okubo’s large family was split up.

She and a younger brother were sent first to Tanforan detention center, a former racetrack in San Bruno, Calif., where they slept on sacks stuffed with hay, in a horse stall that smelled of manure. Okubo’s sketches documented it all—from the moment they were forced to leave Berkeley with their luggage piled up on the sidewalk, to the indignity of Tanforan.

In May 1942, Okubo and her brother were transferred to the Topaz concentration camp in Utah. She would continue to draw thousands of scenes of daily life, teach art classes, and help create Trek, a literary and arts magazine.

For Okubo, there was no separation of artist and subject. She is in most illustrations with fellow inmates, bearing a shirt of many crosses. Lining up for vaccines and the latrine, shielding themselves from dusty gales, the inmates weather isolation and uncertainty, anxiety and despair.

After her art won praise outside of camp, Fortune magazine hired Okubo to assist with a special issue on Japan. In January 1944, she left Topaz, and with Fortune’s help, relocated to Greenwich Village in New York City.

Okubo’s work later appeared widely, including Time, Life, and the New York Times, and in renowned museums that drew diverse and influential crowds. She testified before the US Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in 1981. And in 1984, her most acclaimed work, Citizen 13660, was recognized with the American Book Award.

Okubo continued to draw and paint until her death in 2001 at 88.

The Miné Okubo Collection

View the 197 drawings by artist Miné Okubo (1912–2001) which served as the basis for her renowned book, Citizen 13660, printed in 1946 and was the first personal account published on the camp experience.