Boyle Heights—Audio Diaries Project

Through the Audio Diaries project, a teen examines the wartime removal of Japanese Americans from her Boyle Heights neighborhood.

The following is an edited transcription of an audio program created by a high school senior in a school near East Los Angeles. A total of 25 students from Theodore Roosevelt Senior High School participated in the Japanese American National Museum’s Audio Diaries project, produced in conjunction with the upcoming exhibition about Boyle Heights. Audio Diaries is generously funded by the California Council for the Humanities and the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

Someone Like Me

My name is Elva Escobedo. Recently I had the opportunity to meet someone who, like me, grew up in Boyle

Heights and attended Roosevelt High School. After living in Boyle Heights all his life, Hank Yoshitake was evicted from his home simply because his ancestry was Japanese.

On December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor, Hawai‘i, was bombed by Japan. Hank, now a 76-year-old World War II veteran, remembers:

That morning we were in Sunday school. We went to Evergreen Baptist Church on Second and Evergreen. My dad was picking us up; we were coming home. We heard some rumbling at church about something that happened. My dad was in a rush to get us home. On the way home he told us that Japan had bombed somewhere in Hawai‘i.

Almost 60 years after that horrifying day, I could still see the shock from this news in his face. He did not know what was going to happen to them, but he understood that his would never be the same. From the sound of his voice, I was able to see that it must have not been easy for him to go back and remember that day.

My Mother was sitting in front of the fireplace surrounded by photo albums, and what she was doing was, she was going through photos, photo albums, pictures of her relatives, parents, her brother and sisters. In the fireplace she was destroying the pictures. And so I sat down with her and she would take out a picture, look at it, and throw it in the fireplace. She was destroying any so-called connection between our family and Japan.

I could see through his eyes that he still feels deeply hurt, remembering his mother’s pain and family history. To think of having to

burn my lifetime memories and my family history, knowing that I would never again have them, and at the same time feeling that I must destroy them. . . .I could see the close relationship he had with his mother. And how miserable it must have felt to have to burn your personal treasures for the safety of your family.

The community rapidly began to change. It was no longer a community where there was no racial tension. Now the Japanese had become a threat.

Eddy Kurushima, a Japanese American [who resettled in the Boyle Heights area after the war], also recalled what happened during this time.

There at the market, we knew that people there were from all different ethnic groups. They were very friendly to us, but along the way we started getting calls; they were calling us all kinds of name like, “Japs, what are you doing here, you should go back to your own country. Dirty Japs.” Things like that.

What hurt them the most were not the words that came from those insults, but instead hearing their own neighbors saying to them.

Soon Executive Order 9066 was issued. Japanese families had only six days to report to their assembly centers and could only take with them what they could carry. Everything else had to be left behind.

Fear is one of the biggest things when you go into camps, fear of what could happen next. The door closes behind you, and that’s like you can’t leave anymore. —Eddy Kurushima

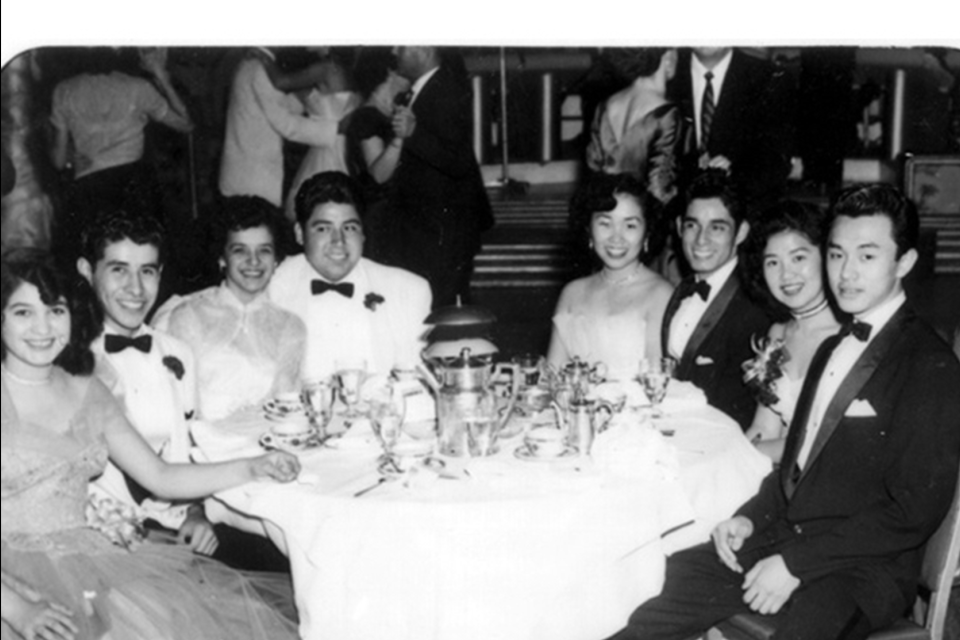

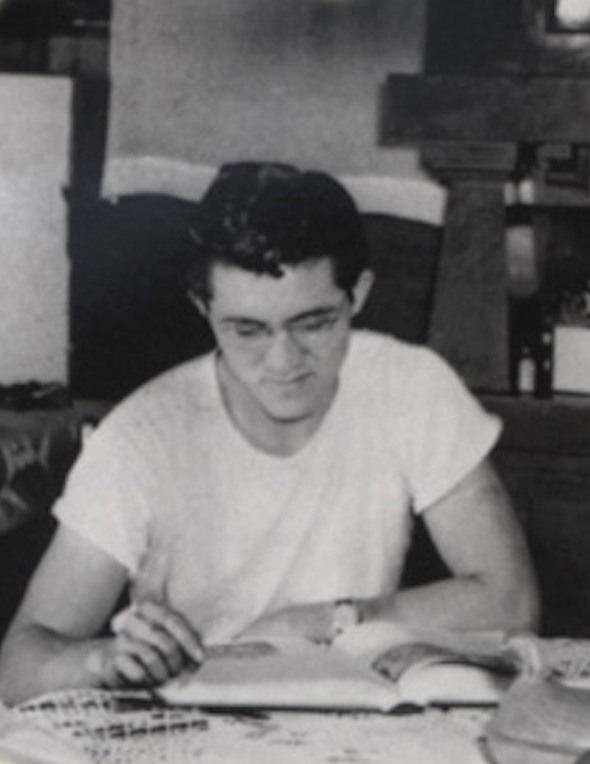

Courtesy of Henry “Hank” Yoshitake and Family

It was not enough to have lost everything they had struggled so much to gain—their homes, valuables, friends—but to make it worse they were locked in internment camps where they were surrounded by not knowing what would happen next.

When I began my interview, it was not logical to me that they would go to war alongside the U.S. after what had been done to them, but that was exactly what they did. Many Japanese volunteered to fight in the war, where they became the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a segregated unit formed of only Japanese American from the internment camps and Hawai‘i. These men suffered 9,000

casualties and accumulated 18,000 individual citations for medals. And they did all of this for the country that had turned its back on them. The only reason for taking such a stand, according to Hank, was for their parent’s safety—at the same time they fought the prejudice that had haunted them all these months. They proved that they could be loyal to a country that had been disloyal to them.

During my interview, I repeatedly asked Hank if he would go to war again if he could go back in time. But he kept asking me to repeat my question. And I asked myself, couldn’t he hear me? Or was he avoiding my question?

Today, years after it happened, he could still remember the awkward feeling he felt when the same [military] that had taken him out of his home was now helping to move back into his home. And I [wonder], were they trying to make up for what they had done years before?

Epilogue

Regrettably, Henry “Hank” Yoshitake passed away on June 1, 2001, a week before Elva’s program was presented at the Japanese American National Museum.