1907–1985

George Hoshida was born in Japan in 1907. In 1912, at the age of four, he immigrated with his family to Hilo, Hawai‘i. It is important to note Hoshida’s age when he made the journey across the Pacific. Although his entire adolescence and adulthood was spent in Hawai‘i, Hoshida was forbidden by law to become a naturalized citizen. Unlike migrants from Europe, immigrants from Asia were restricted from naturalization because of race until 1952.

George Hoshida was born in Japan in 1907. In 1912, at the age of four, he immigrated with his family to Hilo, Hawai‘i. It is important to note Hoshida’s age when he made the journey across the Pacific. Although his entire adolescence and adulthood was spent in Hawai‘i, Hoshida was forbidden by law to become a naturalized citizen. Unlike migrants from Europe, immigrants from Asia were restricted from naturalization because of race until 1952.

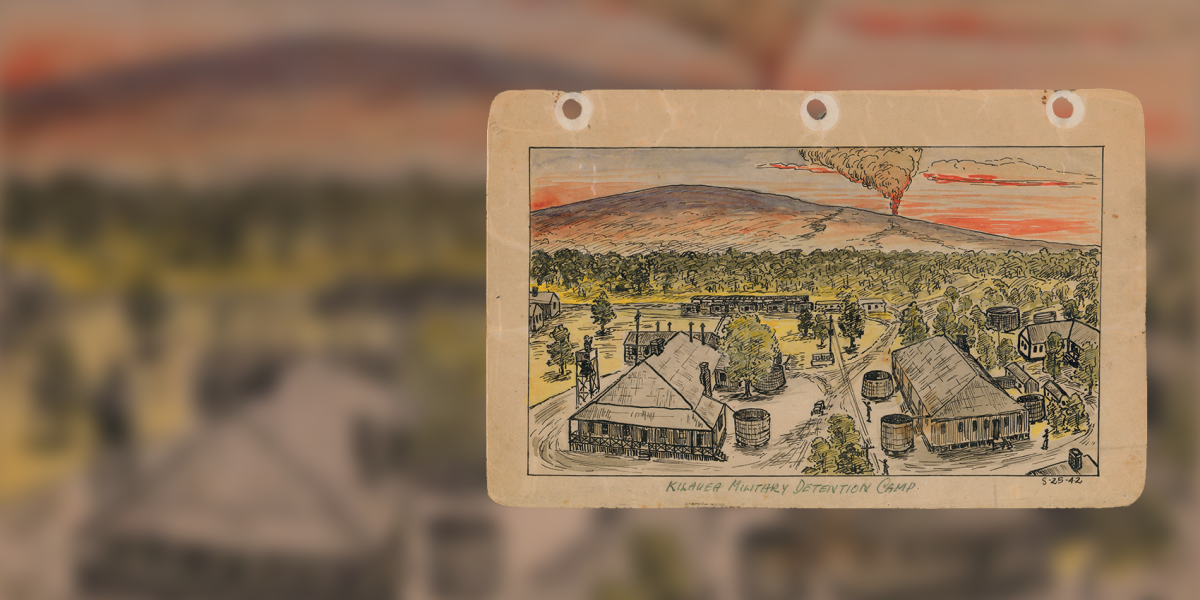

A self-educated man, Hoshida’s formal education ended when he graduated from junior high school (he received his GED after the war). Hoshida then went on to work for the Hilo Electric Light Company, married, and started a family. He was also involved in his Buddhist temple and had a keen interest in judo. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hoshida was considered “potentially dangerous” due to his community involvement. Although he professed little interest in international politics, the practice of his Buddhist faith, his leadership in his temple, and his interest in judo deemed him “suspicious.” Hoshida was first incarcerated in the Kilauea Military Camp in Hawai‘i, and then subsequently taken to the Justice Department camps at Fort Sam Houston in Texas, and Lordsburg and Santa Fe in New Mexico.

During the first two years of his incarceration, Hoshida was separated from his wife, Tamae, and four daughters, Taeko, June, Sandra, and Carole. Taeko was severely disabled and died during his absence. When Hoshida was finally reunited with his family, it was only under the terms of incarceration in the War Relocation Authority concentration camp in Jerome, Arkansas.

While Hoshida was incarcerated, he cultivated a long-time interest in drawing. He filled notebooks with drawings and watercolors of his time behind barbed wire. He drew portraits of fellow inmates, depicted scenes of daily activities, sketched the surrounding camp environment, and used his skills to teach other inmates. His detailed visual diary provides an extensive and personal record of his experiences. Hoshida drew for his own consumption, but his carefully preserved drawings and watercolors helps us reconstruct this critical time in American history.

In December 1945, Hoshida and his family returned home to Hilo, Hawai‘i. In 1959, Hoshida, along with his wife and daughter Carole, resettled in Los Angeles where he worked as a deputy clerk in the municipal court. His daughters June and Sandra would later relocate to Los Angeles. After retiring, Hoshida returned to Hawai‘i where he wrote and published an autobiography entitled, Life of a Japanese Immigrant Boy in Hawaii. George Hoshida died in 1985. In 1996, led by his daughters Sandra Hoshida and June Honma, his family donated his sketchbooks and letters to the permanent collection of the Japanese American National Museum.